A new perspective on pneumonia: what does our body tell us about the cause?

Effectively treating a severe case of pneumonia is often challenging. Identifying the pathogen behind it can be difficult. PhD candidate Ilona den Hartog tried something new: ‘We searched for answers in substances our own body produces.’ PhD defence on 17 September.

When someone is admitted to the hospital with severe pneumonia, doctors immediately administer antibiotics effective against various bacteria. Den Hartog:‘But in a significant number of cases, a virus is the cause, or it's a bacterium that’s less or not at all sensitive to the chosen antibiotics. In both situations, the antibiotics don’t work well. It’s a shame that they are still given.’ It’s a shame for the patient because the antibiotics are ineffective, and a shame for society as they can lead to bacteria becoming resistant to these commonly used antibiotics.

A culture often doesn’t provide a clear answer

To identify the pathogen causing the pneumonia, doctors culture some lung mucus from the patient. The results take about two days and often don’t provide a clear answer. ‘In more than half of the cases, the pathogen is never found, which makes it impossible to tailor the treatment further to the patient,’ says Den Hartog. ‘We wanted to fill that gap.’

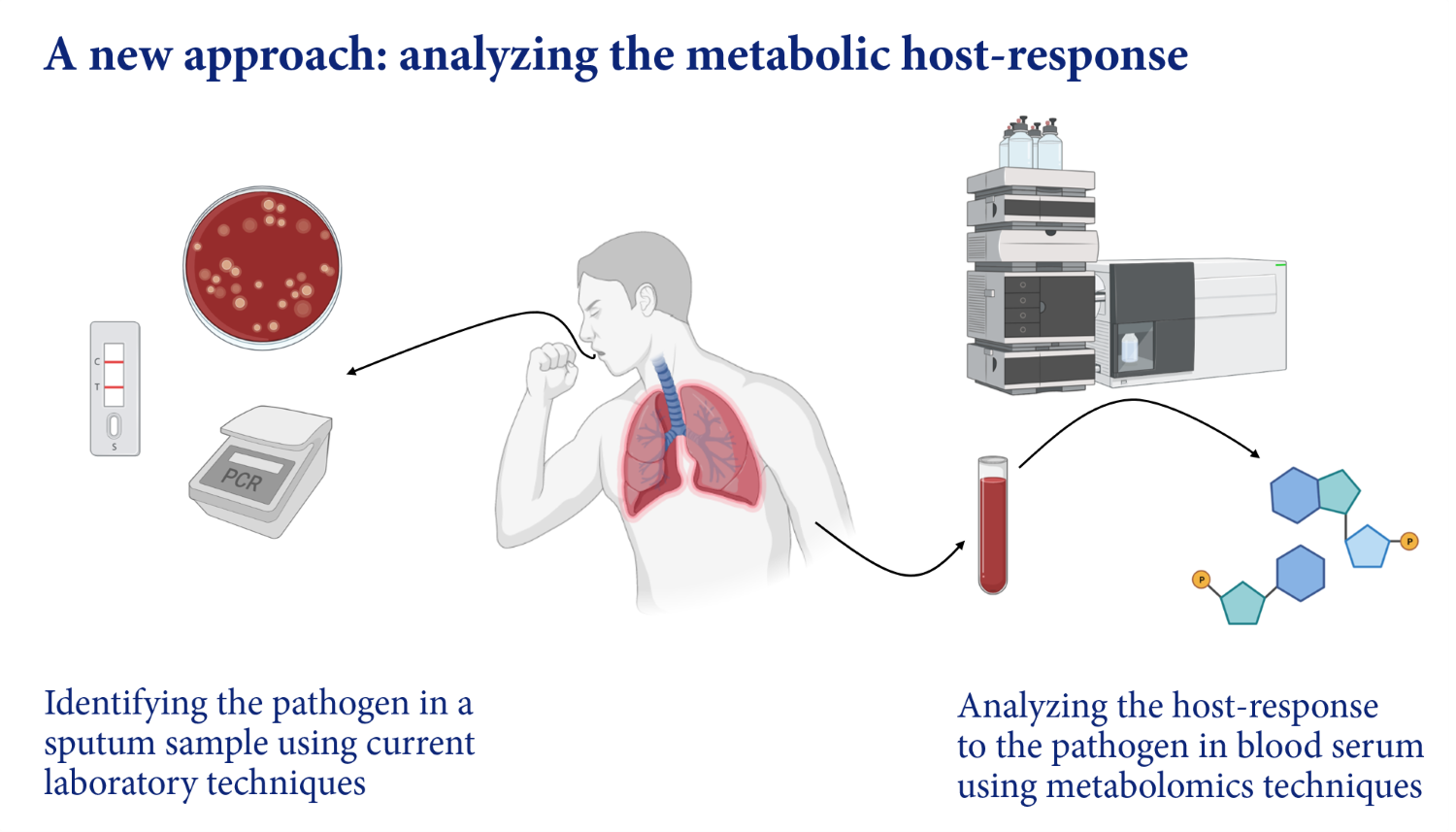

Den Hartog’s supervisor, Coen van Hasselt, received a grant from ZonMw to research this using the relatively new field of metabolomics – see the box below. This research was conducted using a set of blood samples from pneumonia patients, made available through a collaboration with St. Antonius Hospital in Nieuwegein. Van Hasselt explains that diagnostic tests have so far focused on finding bacteria to identify the cause of pneumonia. ‘We wanted to determine the cause through substances that our own body produces in response to the infection. Could we tell, for example, whether a virus or bacterium is involved?’

Metabolomics – What is it?

In studies on genes, scientists refer to genomics. Research into proteins is called proteomics. For about the past decade, there has been growing research into metabolism to answer various (medical) questions. Metabolism is an umbrella term for all the conversions of one substance into another within our bodies. Research into all these thousands of substances is known as metabolomics.

Which organism is the pathogen?

The researchers wanted to find out which organism was the pathogen and looked for clues in the substances our body produces. This required expertise from various fields. Van Hasselt comments that they needed someone who could bring all those areas of expertise together. ‘Ilona studied Biomedical Engineering and enthusiastically and pragmatically tackled the clinical problem of pneumonia in the hospital. She was the true linchpin.’

That network included expertise from the clinic, with previously collected blood samples from pneumonia patients. Den Hartog also collaborated with the Leiden Metabolomics & Analytics Center, led by Professor of Analytical Biosciences Thomas Hankemeier, who has extensive experience in identifying metabolites, i.e. substances produced by the body. Den Hartog: ‘We identified 347 metabolites in blood samples from three groups of several dozen patients. These were people with a pneumococcal infection, an infection from an atypical bacterium, and a viral infection.’

Hopes for a rapid test

Naturally, Den Hartog had high hopes of developing a simple test that could quickly and cheaply detect one or a few metabolites in the blood and immediately indicate the type of pneumonia. This would allow doctors to start the appropriate treatment straight away. ‘Although we did find three metabolites that provide relevant information, the test required to measure them is no better than the one currently used in hospitals.’

The disappointment didn’t last long

That was disappointing, but thankfully the disappointment didn’t last long, Den Hartog says. ‘Colleagues helped me through it. When I was feeling down, talking about it and brainstorming on how to proceed was really helpful. I was able to see the value of the research again.’ And there certainly is value, Van Hasselt emphasises. ‘Although our test is not better than the current one, combining the two could prove very useful. It’s an interesting basis for further research. Additionally, this research has clarified much about what happens biochemically in our body during such an infection and why some patients become much sicker than others.’

From PhD candidate to technical writer

Den Hartog looks back on her work positively. ‘I have learned how to manage a large project and thoroughly enjoyed collaborating with so many different people, from selecting blood samples together to working in the lab to carrying out the analyses.’ After completing her PhD, she started working as a technical writer. ‘I write manuals for large machines. Again, I collaborate with others: they explain to me how the machine works, and then I write a clear manual.’

Text: Rianne Lindhout