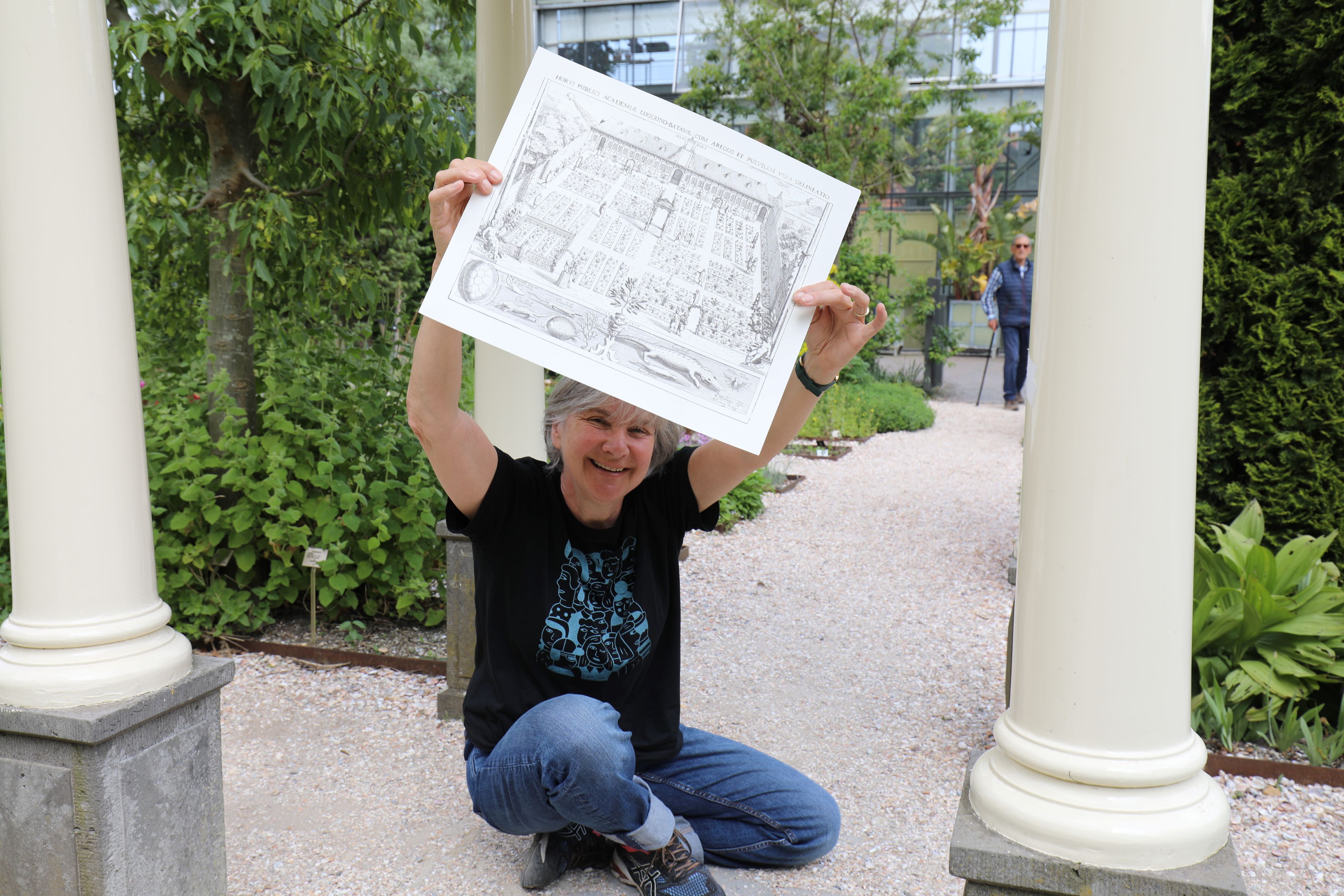

‘When I'm in the Hortus, it feels like I'm walking through the print’

Four prints, ten years of research. Not that she got bored of them, on the contrary. Corrie van Maris, who receives her PhD this week, has always remained fascinated by her 17th-century series, for which she feels so much love. ‘I kept seeing different, new things.’

Before the interview, Corrie van Maris lays the four facsimiles (replicas) neatly on a table in the garden room in the Academy Building, overlooking the Hortus Botanicus. It is a place she likes to look out on; it is a place also depicted on one of the four prints. ‘I work here, so I walk there quite often. When I'm in the Hortus, it feels like I'm walking through the print. Like you have a very direct connection with history. It does a lot for your inspiration. There has to be some kind of spark.’

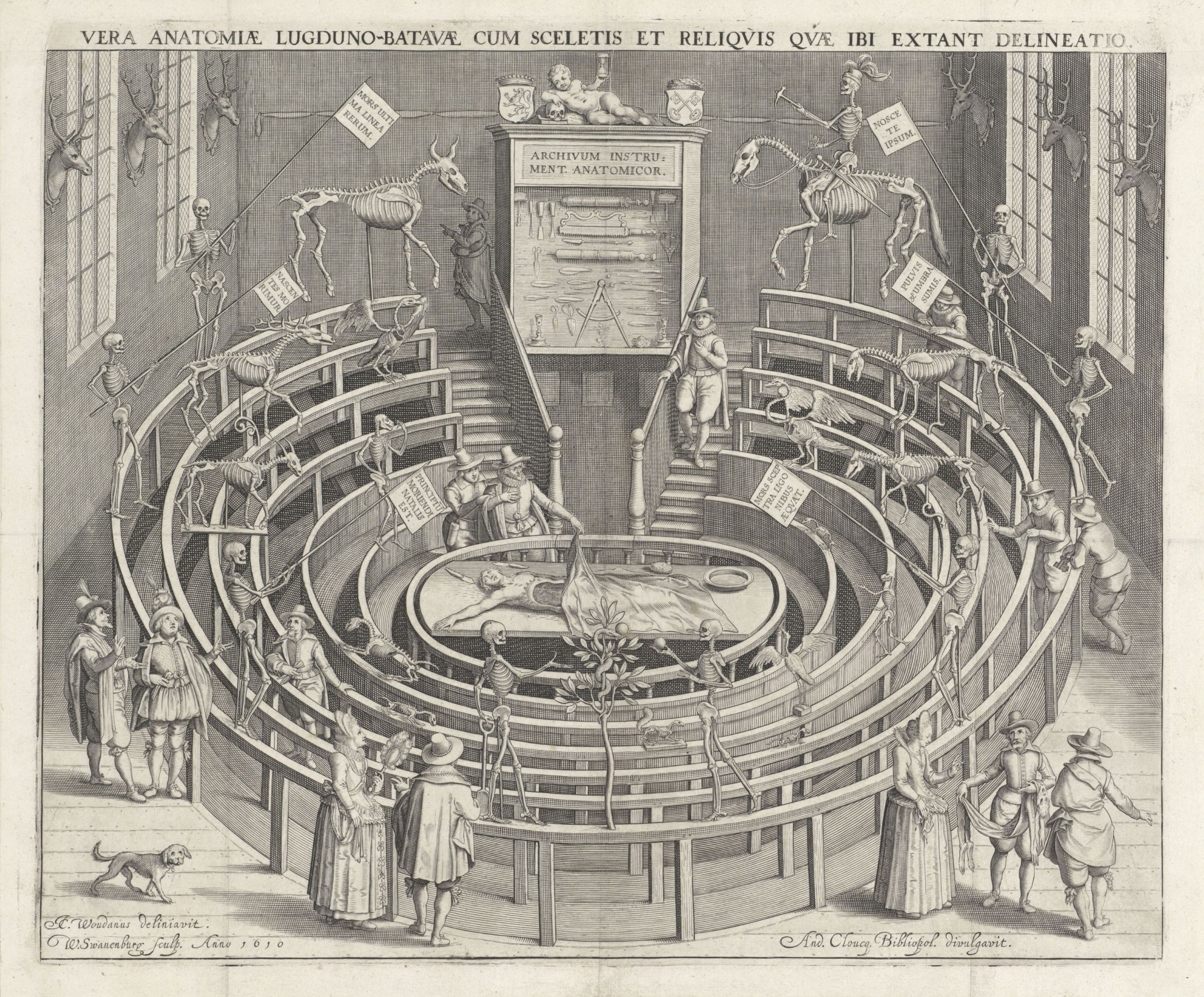

Besides the print of the Hortus, prints of the anatomical theatre, the library and the fencing school also appeared around 1610. Largely produced by two Leiden artists - J.C. Woudanus and W. Swanenburgh - with the aim of attracting people to Holland's university town: Leiden.

What was going on at that time?

‘In 1609 there was a big political change, the declaration of the Twelve Year Truce. You see the city descriptions suddenly emerge. Cities were competing with each other and were keen to show what they had. In 1610 there was also a print of the brand new stock exchange building, which naturally drew people to Amsterdam. What did Leiden have? Textiles, but of course it was a university town, which could be shown through these prints. What nice things did that university have, what did it look like inside, who came there? The university was Leiden's biggest asset.’

How did you came across these prints?

‘When I was about 27, I started working as an attendant at the Academic History Museum - where I work now. Prints were displayed there, I just remember three of them only, not the screen school. I looked at those prints daily and found them very intriguing. They looked like series but were very different, I was very much puzzled by that. I really liked them too, didn't get bored of them. There was also very much written about them. I was very aware that they were important prints.

I never lost touch with these prints. I saw different things all these years, new things. That's nice and that keeps it going. We also had a fantastic institute, the print room on Rapenburg. I felt really delightful in that place, amongst all those boxes full of prints. Printmaking, that has my great love.’

‘You could see skeletons there’

‘The phenomenon of anatomical theatre is very interesting. Bodies were cut there for the benefit of medicine. That happened in winter and in summer something was displayed from the university collection. It had a museum function, it was accessible and you could walk right in. You could see skeletons of people, there were prepared animals and you could see moralistic messages. For example, the skeletons had pennants in their hands with slogans saying something about wealth or a warning: ‘Beware, you are only dust’. People came from far and wide to see, including famous artists such as Hendrick Goltzius.’

What is your background?

‘I studied at the Rietveld Academy and then completed a master's degree in art history in Leiden. As an artist, you look a lot and translate that into images. I also show this in my dissertation; the endpapers feature my art, fragments of images from my 2017 solo exhibition at Pulchri Studio. They reflect the process of this research. When you research the 17th century, you discover that you have to make do with fragments from that era. You never get the picture complete, a lot remains hidden.’

What do you see in specifically these prints?

‘What is striking about these prints is that the structure is quite geometric, which enhances the sense of unity. Circles, squares, rectangles: these are the basic shapes from which images are built traditionally, and still today. In your initial sketch, you do the same; it is a traditional method of observing or ordering something. You have to remember that this is obviously not a representation of reality. It is a presentation of reality, but the distance from the viewer is much greater. When you see them like this, they look like a series, right? I keep the screen school separate because I didn't have that in the picture at the time.’

In the end, your research showed that the fencing school did not actually belong to the series...

‘In 1975, these facsimiles were produced in honour of the centenary and presented as a series of four. All four were also presented in an exhibition at the Rijksmuseum on the history of Leiden University. Professor and writer Willem Otterspeer interpreted it as: symbolically it runs analogously to the four seasons or juices.

Yes, you can give a symbolic value to the number four, which for me as an artist is far too traditional. The new trend is just looking at what you see and not interpreting it directly, but looking as objectively as possible. That's what I did at fencing school.

You see: the differences are lol. First, the colour, the fencing school is quite dark. The figures are bigger, they are also different in anatomy with big ears and noses, and worse in quality. The perspective is also wrong with the fencing school, just look at the squares. The fencing school was always out of tune. A different hand of engraving. That the fencing school was made later I could argue later.’

Read more below.

Special: the role of women

‘Women were excluded from education, but are shown in two prints, the theatre and the garden. What was the reason for Woudanus? In later copies they were omitted, only reappearing in 1716. The women in the theatre are dressed very richly, so perhaps there is this moralistic message: it is not about wealth, we are all dust. The man also holds up a piece of cloth, which again may be a reference to the textile industry in which many women were employed. Clearly, Woudanus gave women a role within university institutions. That they are there I think is a feat in itself. I am happy about that.’

You must be very proud of your dissertation.

‘You always want to find more than you find and say more than you say. It's all very relative. I think it's important that an artist has looked at it. I think that, for me, is the most fun thing I can add to this research, what was already there and what is to come. How were they made and what could that tell me. From an artistic point of view. The interplay between art and science is always present and is also topical now. Well, I think I can go into defence in a moment.’

Do you see yourself more as an artist or a scientist?

‘I'm an artist doing a bit of science. It's nice to look for the connection within yourself, is it possible? I don't take that for granted. Can I eventually bring all these fragments I was talking about earlier together into a whole?’

Text: Magali van Wieren

Image: Magali van Wieren & Rijksmuseum

Vermeerderd en verrijkt

The promotion of Dual PhD student Corrie van Maris will take place on Thursday 30 May at 3 pm.

Corrie van Maris telling us about the 4 prints.

Due to the selected cookie settings, we cannot show this video here.

Watch the video on the original website or