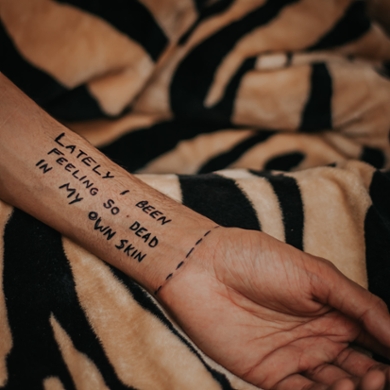

How do you help a child suffering from depression?

What causes depression in a child and how can they get over it? Leiden Professor of Psychology Bernet Elzinga and behavioural scientist Carine Kielstra recently hosted a webinar on the subject of depression in teenagers. The level of interest was overwhelming.

On the one hand distressing and on the other, heart-warming and engaged. That's how Bernet Elzinga, a specialist in stress-related psychopathology, described the seven hundred registrations (half of them parents, the other half professionals) for the webinar on depression in teenagers (10 to 17-year-olds). Not everyone could participate but luckily, the webinar can be still viewed (see column to the right).

How do you recognise depression in a teenager?

Depression in a teenager isn't always easy to recognise. Sombre thoughts can't necessarily be seen on the outside and sometimes a child seems happy among friends, but are mainly gloomy and listless when they’re at home. It's also made more difficult by the fact that depression in teenagers goes hand in hand with behaviour that teenagers often display anyway.

What is depression actually?

Depression is hard to imagine for people who have never experienced it:typically it means always seeing the surroundings and the world as black and feeling pessimistic inside too. A person who is suffering from depression is troubled by sombre feelings and is unable to enjoy things they used to enjoy. But depression can also manifest in sleeping badly, poor concentration, not eating or conversely overeating, low self-esteem and thoughts about death (not having to be here anymore). People suffering from depression often have little or no contact with the people around them, instead experiencing isolation and extreme loneliness. There's a wonderful animation by the World Health Organisation: I had a black dog and his name was depression demonstrates how depression can completely control a sufferer and the people around them. But it also shows that you can overcome it.

NB. The World Health Organisation animation was played during the webinar but due to a technical flaw, the screen remains black when you try to watch it in the webinar attached to this article: you have to watch the animation separately.

Common behaviours in teenagers include being irritated or resentful or even hostile, not being able to handle criticism, black and white thinking and/or crying fits. There is cause for concern if these symptoms are serious and last for more than two weeks continuously.

What causes depression in teenagers?

It's often caused by a combination of psychological and social factors. Genetic factors may also be involved but that's seldom the whole story. Teenagers who are susceptible to depression are already more vulnerable because they are afraid of failure, for example, or are shy, have had a loss or some other unpleasant experience.

Another risk factor is having a parent with symptoms of depression. If one of the parents suffers from anxiety or depression, there is a 38% risk of a child also experiencing depression at around age 20 - the risk increases to 65% at age 36. Interestingly enough, heredity doesn't necessarily play a part in this. That was seen in the findings of research carried out with adopted children: just as in the case of biological children, they turned out to be more at risk of developing depression if one or more parents suffered from it. This suggests that depression is not necessarily in the genes but that the example set by the parents and the contact with them are also important.

Depression occurs more often in girls than in boys.

What role do parents play?

Children who are raised with a lot of criticism and judgement if they fail to meet expectations or demands, are more likely to develop depression. The child will start to feel bad, perform even worse, receive more criticism and parents and children end up in a downward spiral. Negative remarks by parents can undermine a child's self-confidence, and comparison with a younger sibling who does things better doesn't help either. Parents can also be overprotective and smother their child, as it were.

Any problems or psychological issues the parents have can play an important part. A parent who themselves suffers from depression – or is very perfectionist - is more inclined to approach the surroundings, including the children, more critically and negatively. An anxious parent can translate their own concerns into excessive concern for a child. A history of neglect and abuse in the parents can also leave its mark on the children.

In general, psychological neglect in children has more negative consequences that physical abuse.

What do children need?

Teenagers are forming their personality. They develop their own ideas, their own opinions, their own plans. In short: autonomy. They need space and want their parents to let them go their own way, even though parents sometimes find that difficult. Friends seem to be most important; the child rebels against the family and the parents. But that's just an impression. Teenagers need their parents to provide that warmth, empathy, contact, commitment and support: staying in contact, continuing to talk and question and trying not to take criticism too seriously. But it doesn’t mean going to the extreme. Clear boundaries and rules are also important. It's healthy for teenagers if not everything works out as they would like: failure and setbacks are part of growing up and it's good if parents give children the chance to try things out rather than immediately condemning 'errors of judgement'. And contrary to what people often think, fathers are every bit as important as mothers. Research is very clear about that. It's essential for a child to have a good relationship with at least one parent.

Another important way in which parents can help a child suffering from depression is to look after themselves and be good to themselves, also in a psychological sense, and be happy together. That way, they create a harmonious environment for the child.

What role do such factors as corona or a divorce play?

Children are resilient. Divorce or social isolation due to corona are factors that can contribute to the occurrence of depression, but children who have good self-esteem and good contact with parents and friends generally get through those situations unscathed, after they’ve made the necessary adjustments. In the case of divorce, the way it is handled is what has the most impact on the children. If the divorce is acrimonious, children are more likely to be damaged than when the divorce is more harmonious.

What if help is needed?

There is a great deal of pressure on the care system at present for young people with symptoms of depression. For both parents and children, asking for help is often a big step and when they do take that step, these days they come up against long waiting lists. Cognitive behavioural therapy is the first choice but, unfortunately, this helps only roughly half of the young people sufficiently. Depending on the attitude of the care provider, parents may or may not be involved in the treatment. This is a missed opportunity, according to Elzinga and Kielstra. In order to improve matters, they developed the Samen Sterk (Strong Together) course together with other colleagues of Rivierduinen (a local mental health authority institute) for parents of a child with depression. The course is based on the proven principles of Positive Parenting (Triple P). The findings of the first pilot groups are very promising, from both the online and 'live' versions: parents are enthusiastic, experience better contact with their children and the symptoms of depression decrease in a substantial number of the children (see 'Looking for help? in the column to the right). All in all, encouraging signs..

Elzinga and Kielstra's next mission is to further improve the course, with input from parents and other colleagues, and make it accessible on a larger scale to vulnerable families. Both scientists hope this will prove to be more than just a drop in the ocean.

Text: Corine Hendriks, in collaboration with Bernet Elzinga and Carine Kielstra

Photo at the top of the page: Jose Pena (Unsplash)